Fun Progamming

I’ve been doing some fun programming on the side off and on for years. I can’t seem to get into things like LeetCode, and struggle to come up with ideas to do something new that will keep me engaged longer than a series of scripts, and came across Project Euler.

Project Euler problems are math heavy problems that you typically need to write code to solve. They start out pretty simple, but quickly get complex and weird. They’ll cover maths that need to be solved with set theory, or geometry, or statistics, or prime number theory, etc., etc., and are best solved by coming up with an appropriate algorithm for the task. In general, any problem posted should be solvable with a few minutes of computer processing with the right algorithm.

Problem 596

So, I’ve solved 150+ problems at this point, and tend to skip around on different problems to solve. One that looked interesting, but ended up being devilishly hard for me to solve was problem 596.

The problem is as follows:

Let T(r) be the number of integer quadruplets x, y, z, t such that x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + t^2 ≤ r^2. In other words, T(r) is the number of lattice points in the four-dimensional hyperball of radius r.

You are given that T(2) = 89, T(5) = 3121, T(100) = 493490641 and T(10^4) = 49348022079085897.

Find T(10^8) mod 1000000007.

First attempt

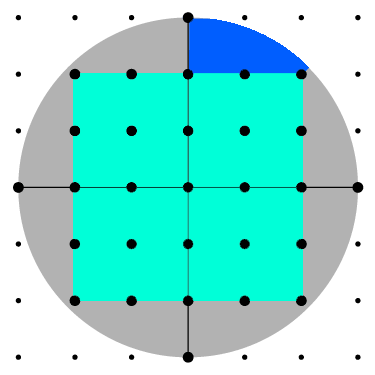

Here’s a quick visualization of the problem as a circle. We’re going to try and count all the points on or in the circle.

For a first pass, I try and put together a simple solution to validate the test case(s). They almost never actually work to solve the problem since they scale poorly. Here’s some simple code that covers every coordinate in the hypercube bounded by radius in_r.

def brute_calc(in_r):

"""iterate through hypercube of radius r"""

ring = in_r**2

result = 0

for x_axis in range(-in_r, in_r + 1):

for y_axis in range(-in_r, in_r + 1):

for z_axis in range(-in_r, in_r + 1):

for t_axis in range(-in_r, in_r + 1):

if ring >= x_axis**2 + y_axis**2 + z_axis**2 + t_axis**2:

result += 1

return result

if __name__ == '__main__':

assert brute_calc(2) == 89

assert brute_calc(5) == 3121

assert brute_calc(100) == 493490641

assert brute_calc(104) == 49348022079085897

While great, this slows down very quickly. It runs in O(n^4) time and wouldn’t be done until long after our sun is burned out and gone.

Other attempts

Cube inside a sphere

So if you take a circle of radius r, and scribe a square inside of it, the sides of the square will be 2*r / sqrt(2) and if you were following the axis up from the origin (0,0), the last lattice point within the square would be floor(r / sqrt(2)). That means that you can effectively count every point within that square and check the space between r/sqrt(2) and r instead. For a hypersphere, that box works out to r / 2 of lattice points that are immediately counted.

Additionally, there are boxed spaces you can immediately rule out as not having any – that is, if abs(x), abs(y), abs(z), and abs(t) are all greater than r // 2 (Quick Python note: // returns floor(x / y)).

While this is great, it’s only a fractional change. It rules out just over half of the problem space, but it’s still a problem set that grows exponentially with the radius, and not a workable solution.

We’re at about 7/16 of the original problem size with this change. You can visualize it here in this circle– the teal square is the first pass, and the blue wedge is the set of unique coordinates translated to the other axes and permutated.

Setting scope

After reducing the space by cutting out the center and the corners, we can try and reduce it more by handling translation across the different dimensions. For example, in a circle, if (x, y) is within the circle, so is (x, -y), (-x, y), and (-x, -y). If you take care to catch situations where points lie on an axis or are the same value so they aren’t double counted (e.g., (1, 2, 0, 0) or (1, 2, 3, 3)), you can take your match and multiply it by 16 to catch all the different quadrants the coordinates end up in.

Similarly, you can reduce by the permutations of the coordinates. If (1, 2, 3, 3) is in the circle, so is (1, 3, 2, 3) and (1, 3, 3, 2), and so on. If the numbers are all unique, there are 24 different permutations.

Between these and the cube within a sphere above, we’re down to a problem space of (1 - 9/16) * (1 / 16) * (1 / 24), or about 0.11% of the original area.

Still O(n^4), still more work to do…

Multithreading

Ok, now let’s say we have a fancy computer with a whole mess of cores that are just sitting there unused while we wait for the heat death of the universe! Let’s put them all to work!

from multiprocessing import Pool, cpu_count

from functools import partial

def calc_inner_4cube(in_r):

return in_r**4 # (2*in_r//2)**4

def x_loop(x_axis, in_r):

ring = in_r**2

result = 0

temp_ring_y = int((ring - x_axis**2)**.5)

for y_axis in range(x_axis, temp_ring_y + 1):

temp_ring_z = int((temp_ring_y - y_axis**2)**.5)

for z_axis in range(y_axis, temp_ring_z + 1):

temp_ring_t = int((temp_ring_z - z_axis**2)**.5)

for t_axis in range(z_axis, temp_ring_t + 1):

if ring >= x_axis**2 + y_axis**2 + z_axis**2 + t_axis**2:

result += 1

return result

def mp_brute_calc(in_r):

"""iterate through hypercube of radius r"""

ring = in_r**2

result = calc_inner_4cube(in_r)

worker_x = partial(x_loop, in_r=in_r)

with Pool(cpu_count() - 1) as poolio:

result += sum(poolio.map(worker_x, range(in_r // 2, in_r + 1)))

return result

Now as long as we have enough system memory to hold a 10^8 Python list in memory, we’re good to go. Oh wait, still O(n^4)…

Final point

All this work refining, and we’ve managed to speed up from the brute force by over 99.95%! …and it’s still FAR too slow. Time for a new approach. How can I reduce the number of dimensions we’re checking across? Is this a problem that I can find an answer to for spheres? Or circles? Gauss’ Circle Problem!

N(r) = 1 + 4 * r + 4 + sum((int(sqrt(r\*\*2 - i\*\*2)) for i in range(1, r+1)))

So, we can’t use this with the shortcuts from the second bit of code, but we can take the first one, adjust the ranges and can combine z and t axes into a single loop:

for x_axis in range(-in_r, in_r+1):

temp_ring_y = int((in_r**2 - x_axis**2)**.5)

for y_axis in range(-1 * temp_ring_y, temp_ring_y + 1):

r = int((temp_ring_y - y_axis**2)**.5)

result += 1 + 4 * r + 4 + sum((int(sqrt(r\*\*2 - i\*\*2)) for i in range(1, r+1)))

Not bad, down to O(n^3)! Project Euler solutions aren’t supposed to be shared for anything after problem 100, so I’ll leave it here. I hope this has been interesting– I’ve found working on the Project Euler problems has made me far more aware of how I’m writing code to run, and what exactly I’m trying to optimize.