Datacenter Migration

At a previous employer, their growth into new businesses had traditionally been through acquisition of other companies. My team was responsible for supporting the production and QA environments for applications servicing the accounting and tax markets. Typically, our role would involve onboarding, releases, building of new servers and environments, decommissioning of old servers, applications, and environments, setting up of monitoring and the overall lifecycle of the application. We would serve as a liaison between the development and DevOps teams and the datacenter services teams (e.g., OS management, database, networking, etc.).

The Project

One of the applications we were tasked with onboarding was a product suite I’m going to refer to as OTP. This was a new product category for the company and industry, due to new market regulations a few years earlier. The acquiured business was about 4 years old at this point and they were running out of a managed services 3rd party datacenter. I was tasked with the planning and orchestration of the move into a company owned and managed datacenter.

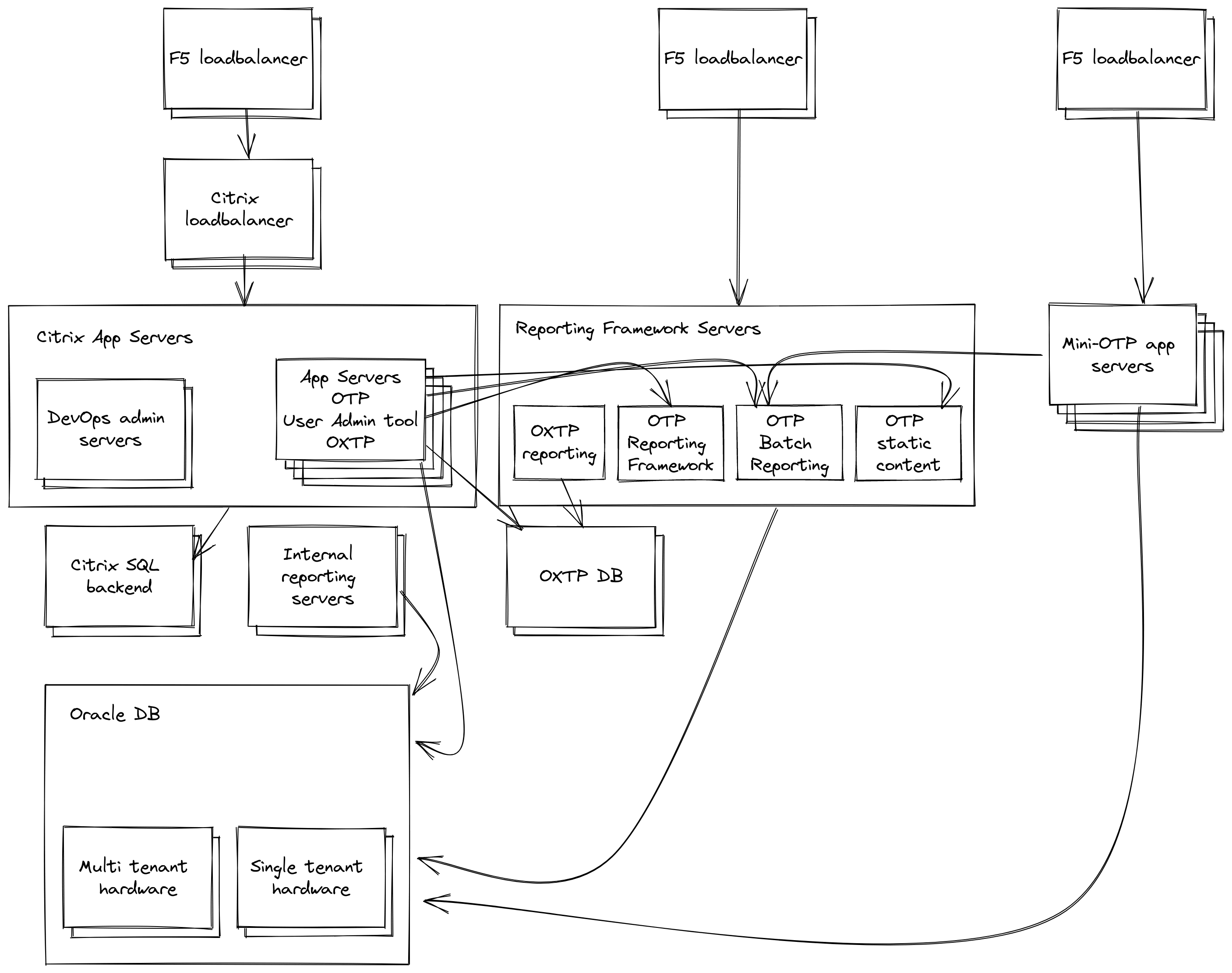

This business was a suite of several different products:

- OTP – “One Tax Product”, the flagship application.

- Mini-OTP – Barebones version of OTP intended for data entry for limited users.

- UTP – “Uther[sp.] Tax Product”, began as a rewrite of OTP as a web-based application, but was transitioned into a wholly new product offering halfway through development.

- OXTP – “Other Cross Tax Product”, custom app for a single customer that became a wholly new product offering.

Due to some contractual obligations, these apps were running multiple different versions of each product in production for different subsets of customers. For example, OTP and Mini-OTP were running around two dozen different versions of code across 4 years of releases, and UTP and OXTP were running 4-6 versions each. These apps were not architected in similar ways—OTP and OXTP were Windows desktop applications that were running in a VDI farm (one with an Oracle DB backend, and the other with MSSQL, and OTP had additional functionality on webservers accessed through a web frame within the application), Mini-OTP was a minimal subset of OTP functionality running in a Tomcat instance across Linux servers (and sharing the OTP database), UTP was a Tomcat application that had custom Java daemon helper processes for managing data (e.g., ETL) into a MongoDB database for reports in addition to an Oracle DB for customer data.

The Setup

When I was brought on to help drive this migration, most of the institutional knowledge for the applications had already left the company—the entire DevOps team had quit, as well as several key developers. Several groups of leadership from the datacenter operations business unit had been out to their remote office in New Jersey to try and build a relationship but all their interactions were still very acrimonious. There were regularly heated arguments over any and every attempt to find common ground and to plan out what their application migration would look like, and no progress had been made yet. With that history in mind, I was flown out to their office to build a relationship with the former call center staff that had been appointed to take over for the DevOps team, integrate them into my application support team, and to start building out knowledge of the applications and operations to make any sort of headway into supporting their business.

On the first day I was in their office, I met with the teams and started to sit down and work through what information and runbooks were available and to start to get a general lay of the land. That afternoon, while working through the application’s architectures, we were interrupted by another member of the call center staff that the UTP application had gone down and they were unable to get it back up and running. I took the opportunity to take what they’d done so far, what the error messages were, and start walking through the architecture with them to track down the problem.

Walking through it step by step, they guided me to quickly draw up the applications functions on a whiteboard and how work flowed through the system. We quickly found that:

- They had no errors on the web tier of the application

- The ETL processes were throwing error messages across all parts of

the process and all versions

- The errors persisted through a service restart

- MongoDB was showing no errors

- The Oracle DB was showing no errors

- They were able to verify that transactions involving the DB were completing successfully.

As we mapped it out how these pieces fit together, I was able to point out to the team that while MongoDB was not giving any errors, that was the only common piece across all the error messages being presented and asked what steps can we take to verify its health? It came out that there was no knowledge on what it did or why it was there. It was implemented by a now-former developer as part of the ETL reporting process. I asked to check out the server directly and quickly discovered that the filesystem had filled up—reports were being generated, loaded into MongoDB, passed on to the next step, but never cleaned out of the queue. With no one having any knowledge of how to manage MongoDB, I quickly found a stop gap solution to clear out the database—clear out all documents older than today’s date. After verifying that data-loss in this piece was acceptable since the documents were only used in a temporary fashion, I ran the commands to clear up space and we were able to get the application up and running again. After a few hours monitoring the disk space on the server, we were able to verify that the rate growth meant it would be months before the issue would recur and were able to put bug fix request in the developer’s queue to remedy.

This ended up being the spark to build a positive relationship with the business. They had been so slammed with day-to-day issues like this and weren’t sharing that these were happening that it hadn’t been communicated clearly that I (and my team) were there to help them as their partners to help solve these problems with the applications and ultimately make the business more stable and reliable. I spent the rest of the next two weeks in the office with them going over all the applications and their many parts in as much detail as we could fit in and was able to return home with far more information to work with than any of us had before.

Working the Project

Returning home from my site visit, I was given a new direction and goal—over the next 12 months, I would build out and test all the applications in the company-owned datacenter and plan for a migration at the end of that window. Additionally, the new DevOps team from the business would be rolled into my existing team. I set our first milestone—get OTP 9.20 up and running successfully (the dozens of versions running in production varied between 5.0.x and 9.20). Over the next 9 months, I met with the developers, the new DevOps engineers, QA testers, and the help desk staff daily as we worked through installation, configuration, and behaviors of the application. We’d meet multiple times a week with project managers and leadership from the business as well as the datacenter operations teams to go over progress, blocking issues, and the ongoing business of the applications (as regular issues and releases continued to progress in parallel to the migration). At the end of the 9 months, we reached a point where we’d managed to get most functionality working for that single version of OTP, but it was becoming clear that we weren’t going to finish within 12 months, as the remaining applications and sub-versions were far from being up and running. I brought 4 contractors into the project at this point to help with the workload, and the migration was pushed out for another 9 months. I also obtained:

- A tech writer to help document runbooks, architectures, processes, etc.

- A Linux systems administrator to help with the setup, administration, and automation for UTP and Mini-OTP

- A Virtualization/Windows administrator to help with setup, administration, and automation for the desktop app portion of OTP

- A Windows administrator/generalist to help with the IIS and ‘other’ portions of the applications

Additionally, both the business and the datacenter operations groups dedicated a project manager to help with the orchestration—what are our blocking issues, who else needs to be brought in, what leverage can be applied to make certain tasks go faster, etc.

With more people involved in the migration, my role transitioned into a project lead—I would find and assign tasks, assist the team with their tasks, and dive in on tasks that were particularly complex and/or of high priority. The large number of versions running brought up a lot of issues with versioning of their dependencies—ODBC driver versions that would work for some versions would work for others, and the installers would overwrite other versions if they weren’t applied in a specific order. QA testing would pass on versions, and then fail in previously undocumented ways on other servers. As part of the transition, we were also migrating up two versions of Windows Server, and had similar issues with .NET and it’s required assemblies that had not been documented in any of the application information. Every week brought new challenges to solve for everyone involved.

As the business was an acquired startup, the applications were not designed with scalability in mind. There were multiple issues around how this played out, but a prominent issue was that about half of the customers for Mini-OTP and UTP were single tenant. They would have dozens of customers each having their own custom configured web application (packaged into a WAR file) running in Tomcat for the application, with hardcoded unique connection strings and other customizations within the package. There was no artifact or configuration management at the time, so the Linux admin contractor that was brought on and I worked on creating a script to manage updating the hundreds of WAR files for the migration. The script would traverse the appropriate paths within the Tomcat installation, and with each file, version it, find the appropriate files within the WAR and strings within the file to update, repackage the WAR, and then force a redeploy in Tomcat.

Work progressed at a steady pace for the next 9 months, with me and my team deploying functions, sending them to QA to test, troubleshoot, and worked into a regular rhythm where we would find an issue, solve an issue, and then a new issue would be found, and the cycle would repeat. While the Linux contractor was working through issues with Mini-OTP and UTP, the other two sysadmin contractors were working through OTP and OXTP, with the tech writer checking in to compile their notes and lessons into a consistent style and voice.

Through regular conversations with the business, my team and I targeted specific versions of code that were causing the most issues, and the business worked with the customers to get them upgraded as much as possible and were able to eliminate about half a dozen versions of code (v7.x specifically had irreconcilable issues we were never able to pin down) by migrating them to newer application versions.

During this time, we also started planning out the migration date—what days worked with known blackouts, contacting key customers, steps and order for the migration, what parties had steps and what they would involve, and what criteria constituted a successful failover vs forcing a rollback.

For the migration, several leaders from the business flew from their office in NJ to MN, and representatives from all the parties involved in the cutover setup in a war room at the office. We started around 9pm CT in the evening with shutdowns and putting up offline notifications, and began with application and database cutovers, which would take hours to complete. Around 2am CT, key functions were up and running again, and pieces were handed of for QA testing as they came online. We concluded the migration at 7am CT when all key functionalities had been tested and verified as working, and while there were issues remaining, they were all minor enough that they could be fixed in the coming weeks.

Retrospective

The impact of completing this project was a cost savings of over $1 million per year in hosting costs and significantly improved uptime—from more than 24 hours of impact from infrastructure maintenance and issues to less than an hour per year (~99.5% to 99.99% uptime). The automation and tooling developed in the migration made future releases go more smoothly, monitoring tools available in the new datacenter gave better visibility into application health, and the scrutiny from poring over the applications in such detail allowed us to find and remedy multiple security vulnerabilities. The improved relationship between the business and datacenter operations helped each better anticipate the other’s needs and opened the door for additional integrations between OTP and other company products.

I learned a lot about managing without influence—working with teams and individuals that have no organizational reason to help, working with individuals that actively don’t want to help, and how useful it is to approach these interactions by framing it as ‘what’s in it for them’. This really made me examine what it means to be a leader vs a manager, and the example I wanted to set as a leader. The business learned to better collaborate with outside teams and have more open and honest communication across organizational boundaries, and the datacenter operations team started approaching the groups as more of a collaboration and not simply in a top-down manner.